Paying attention to the night sky enhances a sense of season

Peterborough Examiner – January 19, 2024 – by Drew Monkman

Like many aspects of nature, the night sky changes dramatically over the course of the year. Knowing the comings and goings of stars and constellations contributes to a rewarding sense of the season at hand. As just one example, Orion’s supremacy over the southwestern sky is as much a part of winter as snow-covered conifers and juncos at the feeder.

With its host of easy-to-recognize constellations, winter is an excellent time to become better acquainted with the night sky. Because it gets dark early, the whole family can participate. All you need is a star chart or a free stargazing app like Star Walk 2. You should also try to get away from light interference. The farther from built-up areas, the darker the skies. If you have binoculars, bring them along, too.

The north sky

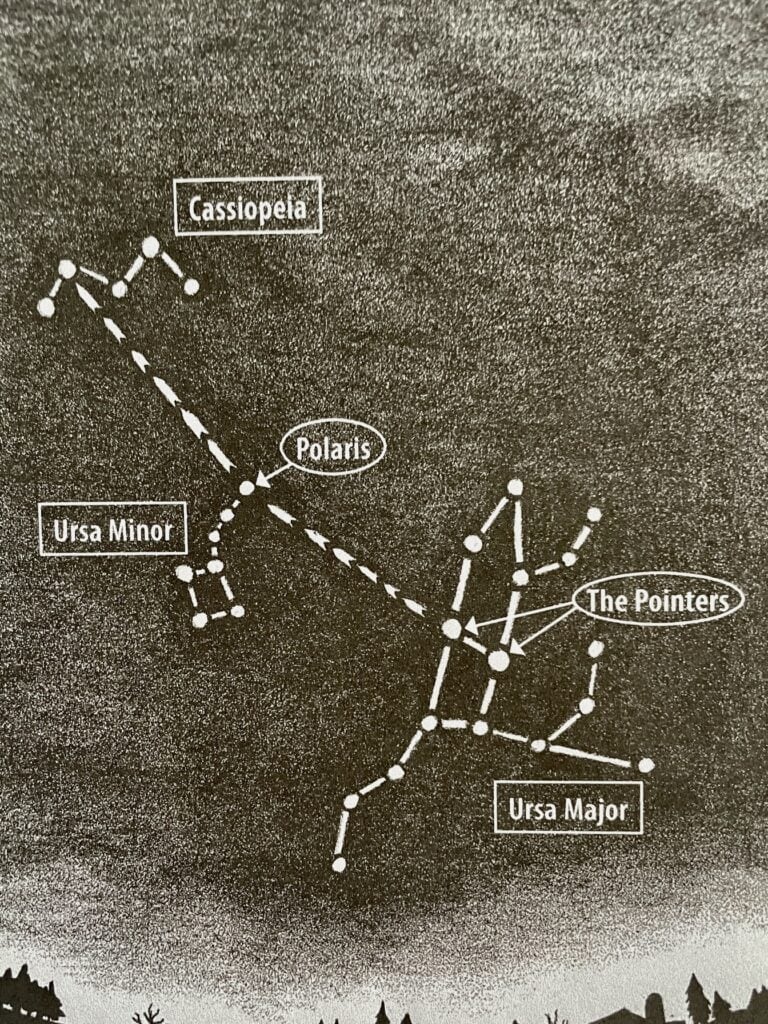

Let’s start our stargazing with the north sky and the so-called circumpolar constellations like Ursa Major. Unlike other constellations which disappear below the horizon for part of the year, the circumpolar constellations are visible all year long. Their position in the sky does change, however, depending on the season and time of night. These constellations appear to rotate around the North Star, Polaris, which sits almost directly above the Earth’s north pole.

The first star pattern or “asterism” to look for is the Big Dipper which consists of seven stars in a distinct, dipper-like shape. It is part of the Ursa Major constellation. On winter evenings, the Big Dipper stands vertically in the sky “on its handle”, just above the northern horizon. Look for the two outer stars in the dipper’s bowl (furthest from the handle) known as The Pointers.

Now, picture a line connecting The Pointers. If you project this line about five times, you will arrive at Polaris. It marks the end of the handle of the Little Dipper asterism. Remember, however, that Polaris is no brighter than the stars of the Big Dipper. It’s fun to try to imagine the Little Dipper pouring its imaginary contents into its big brother.

When you are facing Polaris, you are looking almost due north. South is therefore directly behind you, east is to your right and west is to your left. At our latitude, Polaris is also approximately halfway up the sky. It appears to be stationary, no matter what the time of night or the season.

The other well-known circumpolar constellation is Cassiopeia, the Queen. Its five bright stars form an easy-to-remember “M” or “W” shape, depending on the season and time of night. To find it, simply extend the imaginary line that points to Polaris. Cassiopeia is about the same distance from Polaris as the Big Dipper. This technique of using The Pointers to explore the north sky works at any time of night and in any season.

Half the fun of star gazing is learning some of the legends associated with the night sky. The Mi’kmaqs of Atlantic Canada see the bowl of the Big Dipper as a giant bear and the three stars in the handle as hunters in pursuit. It’s said that the hunters finally catch up to the bear in autumn and its spilt blood causes the leaves to turn red.

Orion, winter’s jewel

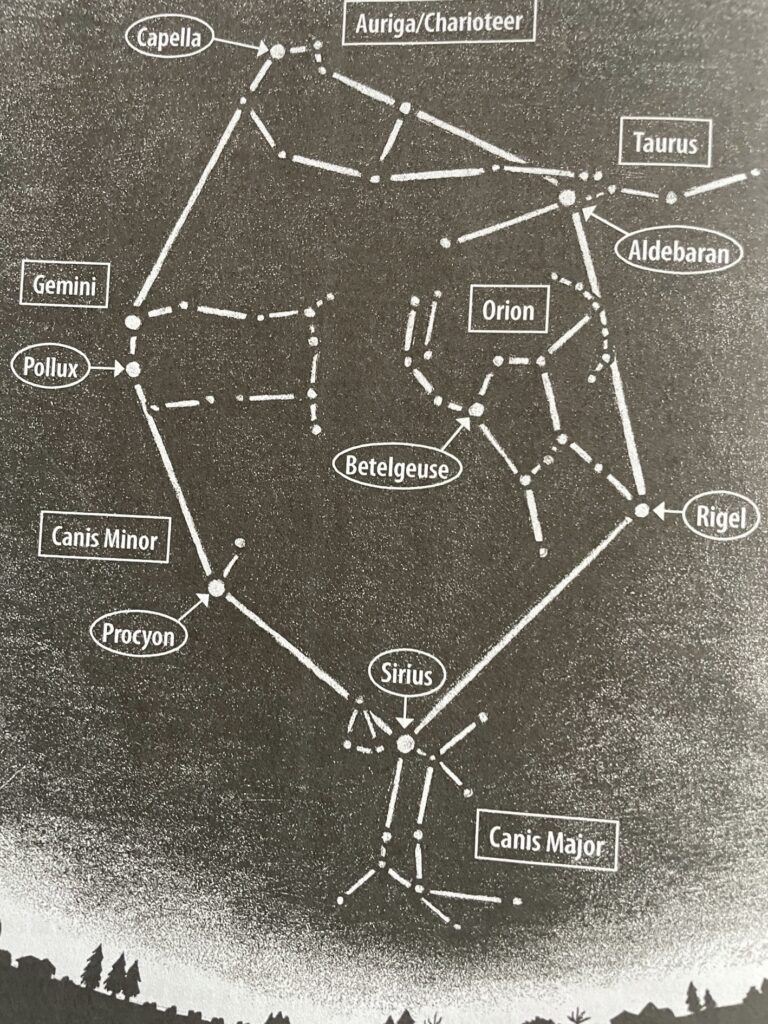

Let’s turn our attention now to the jewel of the winter sky: Orion. With more bright stars than any other constellation, it is both conspicuous and easy to remember. Orion is also part of a group of constellations known as the Winter Six which also includes Taurus, Gemini, Auriga, Canis Major and Canis Minor.

Orion is one of the few constellations that actually looks like its namesake – the famous hunter of Greek mythology. The stars representing the hunter’s shoulders, waist and knees are particularly easy to see. Betelgeuse, the reddish star that forms the left shoulder, is a supergiant, 800 times the diameter of the sun. The lower right corner, representing the hunter’s right knee, is occupied by Rigel, a magnificent bluish-white star 50,000 times as luminous as our sun. Rigel was an occasional destination of the starship Enterprise in the television series Star Trek.

The most fascinating feature of this huge constellation, however, is the Orion Nebula, the brightest of all the nebulae in the night sky. To see it, you must first of all find the diagonal line of three stars forming Orion’s belt. Look next for a string of faint stars below the belt that represent the hunter’s sword. In the middle of the sword, you will notice a fuzzy patch. This is the nebula. Its indistinct, cloud-like appearance is visible through binoculars but becomes spectacular in even a small telescope. You will see “bays and rifts” of stellar material, intertwining themselves around four stars. Parts of this greenish cloud of gas and dust are actually contracting to form new stars.

Orion’s belt is your guide

Orion’s belt also serves as a reference point to other Winter Six constellations. To the right, it points to just below the reddish star Aldebaran, located in the constellation Taurus, the Bull. If you continue a short distance past Aldebaran, you will find a beautiful cluster of stars known as the Pleiades, or Seven Sisters. The stars form a pattern quite similar to the Little Dipper. They also represent “nature’s eye test”. Legend has it that warriors who could see all seven stars were given the jobs of scouts or archers. With the naked eye, most people can only see five or six.

Following Orion’s belt to the left, it points to Sirius, the Dog Star. Sirius is the brightest star in the night sky and the principal star of the constellation Canis Major, the Great Dog. The legs, back and tail of the dog are all easy to imagine. In early August, Sirius rises in the southeast just before the sun. Because the star is so bright and its appearance often coincides with the hottest weather of the summer, this period became known as the Dog Days of summer.

Next, imagine a line running up from the left-hand end of the belt, through Betelgeuse, and arching to the left to a pair of bright stars, situated high in the sky. These are Pollux (on the left) and Castor, the brightest stars of the constellation Gemini, the Twins. They mark the twin’s heads. Gemini is part of the zodiac, a group of 12 constellations that lie along the annual path of the sun across the sky. Between Pollux and Sirius lies another bright star, Procyon. It’s the alpha star of a dim constellation known as Canis Minor, the Little Dog. Don’t worry if you can’t see a dog here!

Planet-watching

The comings and goings of the planets is much more complicated than the constellations since they tend to wander across the sky. In fact, the word “planet” comes from the Greek word for “wanderer”. The easiest way to keep track of them is with a stargazing app.

There’s good planet-watching to enjoy this winter. Venus dazzles as a morning “star” in the southeast. On February 22, you can see Venus and Mars close together in the predawn sky. Jupiter is best seen in the early evening in the eastern sky. Saturn is also an early evening object and is visible above the southern horizon. Any telescope with 40 X magnification or more will provide detailed views of Saturn’s rings.

Take some time this winter to “look up”. The night sky is an integral part of our changing seasons.