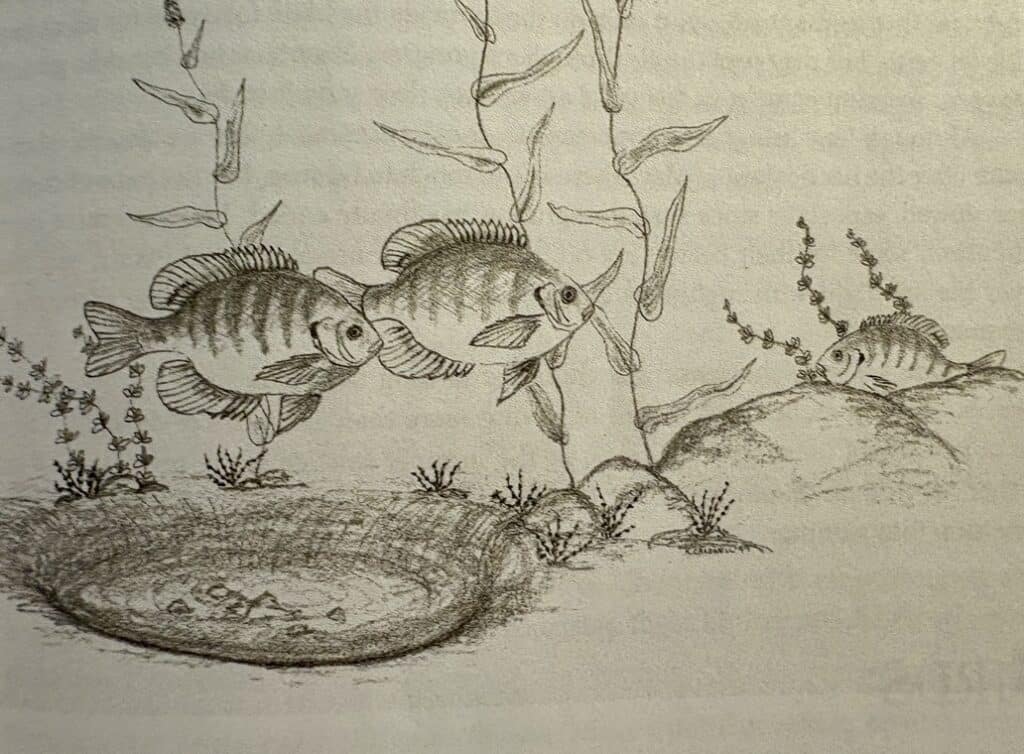

The surprising love lives of pumpkinseeds

Peterborough Examiner – June 27, 2025 – by Drew Monkman

Shimmering in the sunny shallows of lakes and ponds, the pumpkinseed sunfish is a true jewel of our local waters. Shaped like a flattened oval—hence the name—this colourful little fish is anything but plain. Its red-orange belly and wavy stripes of blue and brown give it a tropical flair that’s easy to overlook.

Maybe that’s because we tend to dismiss pumpkinseeds as a “children’s fish”—easy to catch from docks or shallow shores, and just too common to earn much respect. But when you take a closer look, especially during the breeding season, the pumpkinseed’s world is full of drama, strategy, and dedication. Few fish in the Kawarthas lead such fascinating family lives.

season. These small but striking fish are common and fascinating

to watch. (Scott Gibson)

Meet the Family

The pumpkinseed is one of several sunfish species found in our area, along with rock bass and smallmouth bass. Others, like the largemouth bass, bluegill, and black crappie, have either been introduced or expanded into local waters naturally. Bluegills look similar to pumpkinseeds but can be told apart by the lack of facial stripes and a prominent black spot on the gill cover. They’re now among the most common fish in Rice Lake. In fact, pumpkinseeds and bluegills sometimes interbreed and produce hybrids.

lack of facial stripes and a prominent black spot on the gill cover.

They share the pumpkinseed’s breeding behaviour. (Scott Gibson)

Summer romance (and responsibility)

From June into early July, male pumpkinseeds begin the breeding season by building nests in shallow water. Using strong sweeps of their tail fins, they clear away gravel and plant debris to create a clean, circular depression on the lake bottom. These nests often appear in clusters—sometimes as many as 10 to 15 together.

Once the nest is built, the male waits. When a female approaches, he swims out to greet her and attempts to lead her back. If successful, the courtship begins. The pair swims in a tight circle, side by side, their bellies touching. As the female lays her eggs, the male releases sperm to fertilize them. Sometimes, more than one female will use the same nest, and a single nest can end up holding over 15,000 eggs.

After the eggs are laid, the females head back to deeper water. Their job is done. For the males, though, parenthood is just beginning. They guard the nest fiercely, chasing away predators and fanning the eggs with their fins to keep the water oxygen-rich. Even after the eggs hatch, the males remain on duty for another couple of weeks, protecting the tiny fry and even retrieving wandering youngsters by gently carrying them back in their mouths.

Cheaters in the shadows

But not all male pumpkinseeds play by the rules. In fact, the majority avoid the hard work of nest-building and child care altogether. These are the “sneaker” and “satellite” males—clever imposters with very different strategies for passing on their genes.

Sneaker males are small, fast, and sexually mature by the age of two. When a female is spawning with a nest-building male, a sneaker will dart in at just the right moment to release his own sperm. He may get chased away, but the damage—or in his case, the success—is already done.

Satellite males take a more subtle approach. They mimic females in both size and appearance, hovering near the nest and acting harmless. When spawning begins, they slowly slip into the nest and release sperm alongside the territorial male.

As a result, a nest may contain offspring from several fathers. Studies show that in many cases, over half the eggs being cared for by the “honest” male were actually fertilized by someone else.

Who becomes what?

Whether a male becomes a territorial “dad,” a sneaker, or a satellite seems to be mostly determined by genetics, although scientists now believe early environmental conditions may play a role, too. Males don’t change strategies once they’re on a path. The big nest-builders don’t reach maturity until age six or seven, while the sneaky types mature early but rarely live past five.

Even though sneakers and satellites make up about 80% of the male population, they never dominate entirely. If there aren’t enough territorial males around to provide nest care, fewer fry survive. This natural balance helps keep all three strategies in check.

Interestingly, bluegill sunfish—close relatives of pumpkinseeds—use the same three tactics, and scientists have been studying them for decades to better understand mating systems in animals.

Go fish-watching

All of this drama plays out in plain sight if you know when and where to look. Fish-watching can be as rewarding as birding—and all you need is a pair of polarized sunglasses to cut the glare. Try watching from a dock or shallow shoreline with the sun behind you or even go snorkeling. Move slowly and you’ll be amazed how close you can get.

The best time for fish-watching in general is from ice-out to early summer, when sunfish and bass are nesting, and again in the fall when trout are spawning and salmon are moving up rivers like the Ganaraska. The latter can be easily seen in Port Hope. The Kawarthas are also home to a wide variety of lesser-known species like sticklebacks, darters, and minnows—many of which live in shallow water and can be netted and observed up close.

Next time you’re near the water, take a moment to peer below the surface. You might just discover that even the most familiar fish lead lives full of surprises.

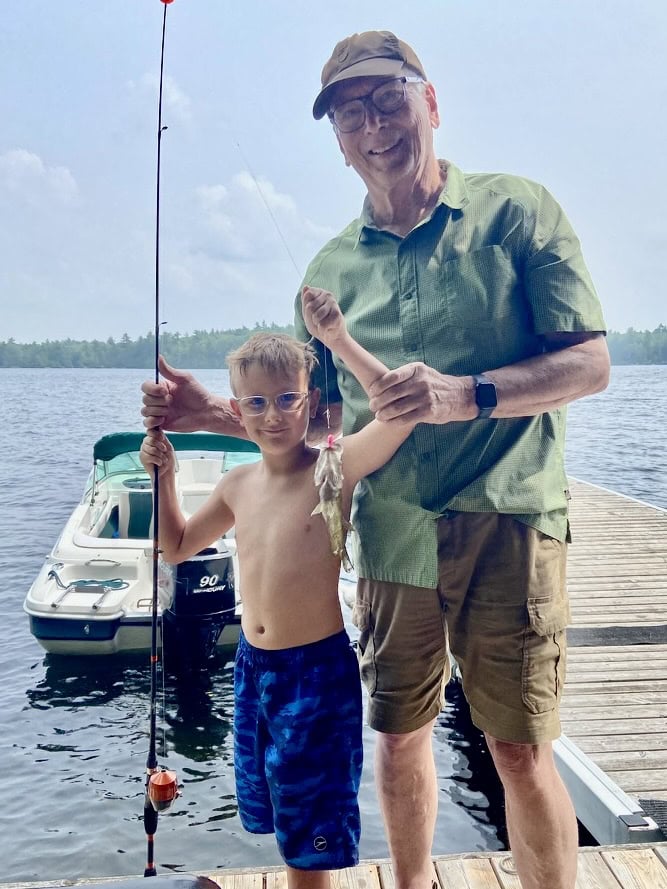

along shallow shorelines. They are often a child’s first catch, like my grandson, Oscar.