The flowers of our common trees are an under-appreciated element of spring’s beauty

A beautiful spectacle unfolds above our heads each spring. The lengthening days and increasing warmth are stirring flower buds that have lain dormant through the long winter months. Where only weeks ago there were just bare branches, the flowers of many of our most common trees now punctuating the landscape and offering up a gentle array of colours and shapes. As the flowers open, tree crowns take on a hazy, pastel appearance, announcing the long-awaited change of season. Make a point this spring of looking up and appreciating this blossom parade that can easily go unnoticed.

Flower parts 101

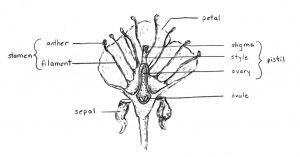

Like the annuals and perennials in our gardens, all trees produce flowers. Their raison d’etre, of course, is to produce seed to assure future generations. Flowers, however, vary in their configuration and can’t be fully appreciated without knowing the various parts. This might require reacquainting yourself with some special vocabulary. Let’s start with a typical or “perfect” (hermaphroditic) flower, such as those of a cherry or apple tree. A typical flower has both male and female reproductive organs together in the same structure. The female part is the pistil, which is usually located in the center of the flower and rises above the male parts. The pistil consists of the stigma (the sticky, widened top), the style (the long tube holding up the stigma) and the ovary, which is hidden at the base of the style. The ovary contains the female egg cells called ovules.

The male parts are called stamens and usually surround the pistil on all sides. The stamen is made up of the anther (the widened, pollen-producing top) and the filament, which is the stem of the anther. When a flower is pollinated (fertilized), pollen adheres to the stigma, and a tube grows down the style and enters the ovary. Male reproductive cells travel down the tube and fertilize the ovule, which then becomes a seed. The ovary becomes a fleshy fruit. Remember this the next time you eat an apple, because you are actually eating an apple flower’s enlarged ovary. Because insect activity is so unpredictable during the often-cool days of April and early May, most early‑flowering trees depend primarily on the wind to spread their pollen.

Not all flowers are “perfect”, however. Flowers may also be unisexually male and only bear pollen-producing stamens (staminate flowers) or unisexually female and only bear seed-producing pistils (pistillate flowers). Unisexual flowers often appear in long, caterpillar‑like structures called catkins. Each catkin contains dozens of individual flowers – all male or all female. Think of a cob of corn and each tiny flower as one kernel on the cob. Some common trees with catkins include willows, poplars, aspens, alders, and oaks.

Because catkins are easily jostled by the breeze, they are a superb adaptation to wind pollination. Let’s take the example of the Speckled Alder, whose catkins light up local wetlands. In the warm April sunshine, they swell into eight-centimetre-long purple, red and yellow garlands, releasing their pollen in golden puffs when disturbed. The female flowers are nestled in small, erect catkins that become cone‑like in appearance when the seeds are ripe.

One house or two?

Like human sexuality, the sex of trees – male, female or both – is complicated. Some species have separate male and female flowers on each individual tree. That is, one branch or twig might male flowers and another have female flowers. These species, along with species possessing the more typical “male and female together” flowers (a.k.a. perfect flowers) are referred to as monoecious (from the Greek, in one house).

However, there are also plants like willows, poplars, aspens, hollies, and Manitoba Maples that have separate sexes, just as animals do. They have male flowers on male plants and female flowers on female plants. These species are called dioecious (in two houses). This means that female trees can only produce fertile seeds if there is a male nearby. Hollies are an example that gardeners are familiar with. An individual holly is either male or female and produces either functionally male flowers or functionally female flowers. The word “functional” is important here, because sterile, reduced-in-size, non-functional flower parts of the opposite sex are present in both the male and female flowers of hollies.

Even within the monoecious/dioecious framework, there are exceptions. In the case of Red Maples, for example, some individual trees are monoecious, and others are dioecious. Under certain conditions an individual Red Maple can even switch from male to female, male to hermaphroditic (perfect flowers), and hermaphroditic to female.

The flowering calendar

Trees and shrubs flower in reliable order each spring. With climate change, however, the dates have tended to become earlier on average.

Late March: Silver Maple, poplars, aspens; Early April: Red Maple, Speckled Alder, Pussy Willow;

Mid-April: American Elm; Late-April: Manitoba Maple, White Birch; Early May: Serviceberry (Juneberry); Mid-May: Sugar Maple, Norway Maple, Common Lilac, Pin Cherry, apples; Late May: Striped Maple, White Ash, Chokecherry; Early June: Bur Oak, Red Oak, American Beech; Mid-June: Black Locust, Black Cherry, Black Walnut; Late June: Catalpa, Small-leaved Linden; Early July: American Basswood

The maples

Each spring, I like to pay special attention to the flowers on maples. The Silver Maple is the first of this genus to blossom, with flowers often appearing as early as March. The fat, bright clusters of red flower buds produce either male flowers with dainty yellow stamens or female flowers with reddish pistils. When the male flowers are ripe with pollen, the whole twig looks yellow. Twigs with female flowers appear all red when the pistils appear.

In early April, Red Maples have their turn. The profusion of tiny, red flowers against the tree’s smooth gray bark is one of spring’s loveliest sights. The flowers have small, red petals, which hang in tassels. The Red Maple wears its name proudly, because all the tree’s interesting features are indeed red: the winter twigs and buds, the spring flowers, the leafstalk and, in male trees especially, the fall foliage. In the Kawarthas, Red Maples are primarily a Shield species. Both Red and Silver Maples attract bees on warm spring days, thanks to their offering of pollen and nectar. They are also pollinated by the wind, however.

A cluster of male flowers (L) from a Sugar Maple. Three female flowers, each with two long styles, can be seen at the bottom on the cluster on the right. (Drew Monkman)

Another member of the maple clan to flower in April is the Manitoba Maple, a somewhat aberrant member of the genus. Not only does it have ash‑like, compound leaves, but the seed flowers and pollen flowers appear on separate trees. This is a very common species of urban areas, taking root in some of the most inhospitable sites imaginable

In the next couple of weeks, Sugar Maples will be flowering. To the trained eye, blooming Sugar Maples are one of the most conspicuous trees in both the urban and rural landscape. The trees glow in a garb of pale yellow-green as countless, long-stalked clusters of flowers hang from the twigs. At a glance, the floral display might be mistaken for leaf-out, but the leaves have usually only begun to emerge when Sugar Maples are in full flower.

The male and female flowers of Sugar Maples can appear on separate trees, on separate branches of the same tree, or even on the same branch in the same tree in the same cluster. There are no petals on the flowers. Clusters of male flowers are 7-10 centimetres long with hairy stalks. Each cluster has 8-14 individual flowers. At the end of each stalk is a bell-shaped, yellow-green calyx. Six to eight stamens extend just beyond the calyx. Most of the flowers low on the tree are male.

Female flowers appear in shorter clusters, measuring only 2-5 centimetres in length. The pistil has two curved styles, which protrude from the calyx. Female flowers are most common higher up in the tree. Within a week or so, the male flowers fall to the ground, leaving a yellow confetti on sidewalks and roads. Female flowers, of course, develop into paired keys, which spin to the ground in late summer.

Norway Maples, which also bloom in mid-May on average, also deserve a close look. The flower clusters resemble giant, lime-green pompoms. The leaves and flowers emerge simultaneously. Unlike the Sugar Maple, the flower clusters are erect, and each flower has five petals. Male flowers are composed of eight fertile stamens, while female flowers have eight sterile stamens and a long green pistil, which splits into a pair of curved styles.

I encourage readers to take some time this month to look more closely at tree flowers. It’s fun to try to see all the floral parts and to determine whether the flower is male, female or a perfect flower combining both. Try to follow the progression on female flowers from blossom all the way to seed, maybe capturing the development with your camera. Nature reveals so much more when you take time to really pay attention.

Arguments for Climate Action

When talking about climate change with friends and family, remind them that a majority of Canadians in every province, except for Alberta and Saskatchewan, are in favour of a carbon tax. A majority also believes that government must lead the climate effort and that individual action won’t be enough. When people say, “Well, what can I do?”, the answer is simple: support strong government action. In addition to a carbon tax, this includes phasing out coal and implementing stronger regulations like more aggressive clean fuel standards. Point out that 70 percent of Canada’s emissions are industry-related. All these initiatives, of course, involve costs to taxpayers – either transparent at the gas pump or hidden when it comes to regulations affecting industry – so paying these costs is “what you can do”.