No matter how you measure it – demand for camping equipment and bicycles, provincial park reservations, traffic on local rail-trails, or sales of feeders and bird seed – the pandemic has led to a huge uptick in the number of people engaging with nature and the outdoors.

If you’re looking for a way to further enhance your enjoyment and knowledge of the natural world – and contribute to science at the same time – you should consider an online identification tool and community science network called iNaturalist. Although I’ve been aware of it for years, I must admit that I’d never taken the time to explore all it offers, namely a universe of information and possibilities. It was thanks to a Zoom workshop in July led by Mike Burrell, a zoologist at the Natural Heritage Information Centre, that I’ve become hooked. In the process, I’ve learned to identify many new species, especially in challenging groups such as lichens, fungi, mushrooms, and beetles.

In short, the iNaturalist app and website is a nature information and identification platform by which you record your observations – be they flora, fauna, or fungi – using photos or even sound recordings. In addition, you automatically connect with other users in the iNaturalist community who can confirm your identification – usually taken from a list of suggestions generated by the app – or propose a different one. All the while, you are creating important scientific data. And, you don’t have to be an expert. Most people start by exploring plants and insects in their own backyard or neighbourhood.

Started in 2008, iNaturalist’s popularity has exploded. In Ontario alone, there are over 40,000 users, and more than 1.7 million observations have been made. About three-quarters of the observations are of plants and insects since these are the easiest to photograph with a smartphone. As of 2019, nearly 3,600 plant species had been logged and 6,000 kinds of insects! Although you can submit photos of birds as well, eBird is a better platform for this purpose.

But iNaturalist is not just about science and becoming more knowledgeable.A reward of sorts is provided. Charts, which rank users based on their number of observations and species, incentivize people to submit more often. This competition aspect is a great motivator and definitely adds an element of fun.

Although the app itself is extremely powerful, you need to visit the website to appreciate all that iNaturalist offers. This includes rich data visualization tools. For a given species, you can bring up pages with a graph of when during the year it can be seen, the total number of observations, and the latest observation. There is also a map page showing where – in Ontario, for example – it has been found. Knowing where and when you’re most likely to see a given species allows you to head out to find it more easily. It’s also fun and inspiring to simply know what other people are discovering.

How to use it

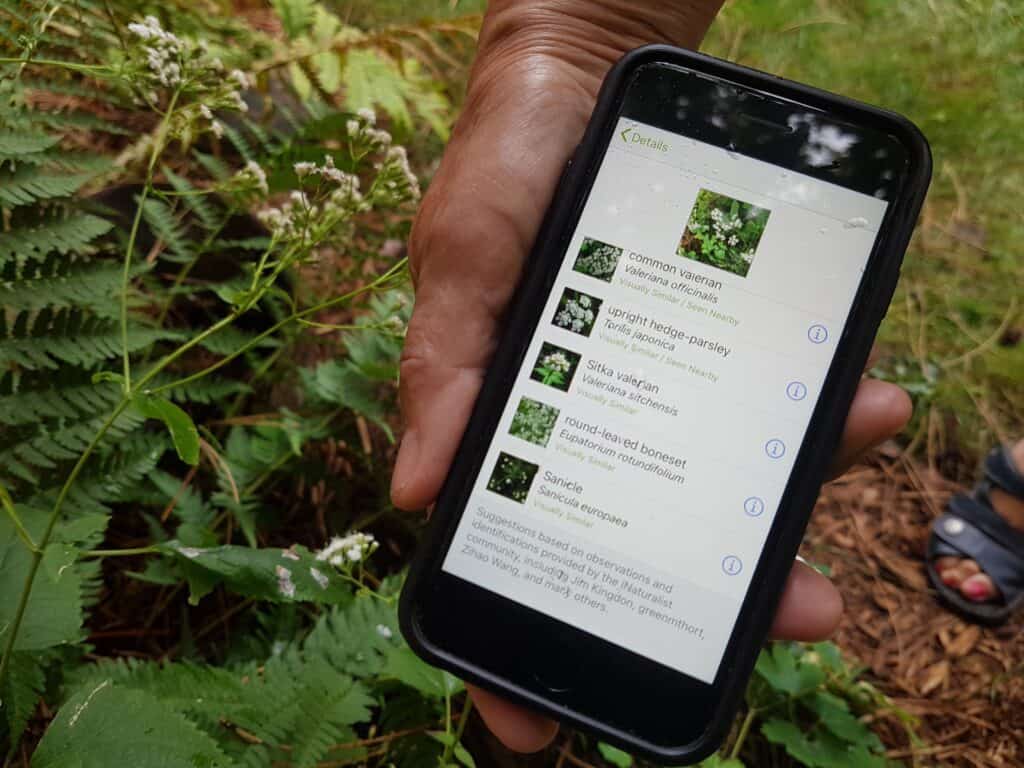

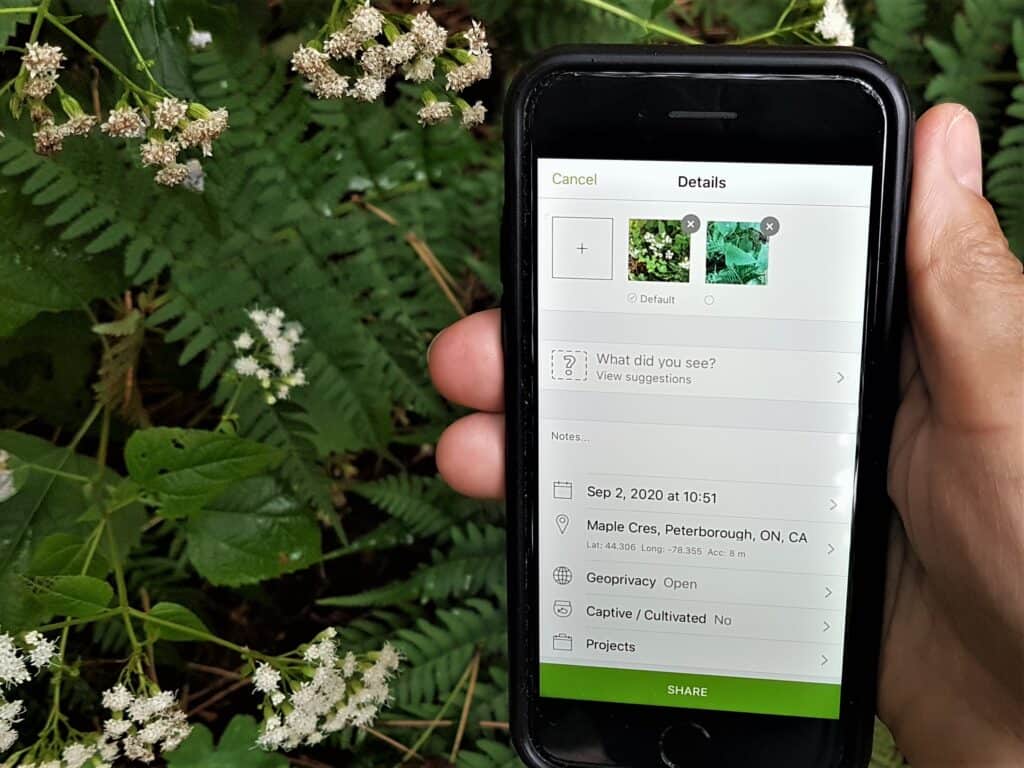

Start by downloading the iNaturalist app on your iPhone or Android or visit the website at iNaturalist.ca. The next step is to create an account. You can then head outside with your smartphone, making sure the location (geotag) function is turned on. The location, however, can also be added manually. Look for a species of interest and take some photos. It’s often best to take several shots in order to show different features – the flowers and leaves of a plant, for example. Your photo will appear on the iNaturalist “Details” page, along with the date, time, and location. Click on “What did you see”, and the app will compare your photo to the iNaturalist photo library. The probable genus along with ten suggested species will pop up. The app will also tell you if the species has been seen nearby. Click on the species that looks most similar and compare your photo to the photo iNaturalist provides. The two will appear on the same screen. You can then select it if you’re convinced there’s a match. If you feel it’s important to add more information, you can use the Notes section. You can also add the observation to a project (explained below) and edit the location visibility if necessary. iNaturalist works even if you don’t have an internet connection. Just click on the upload button and the observation will be saved. Don’t forget to check back to see if the iNaturalist community has confirmed or identified the species.

Review process

iNaturalist is set up as a community network of naturalists in which members can review each other’s observations for accuracy. Users can suggest changes to or confirm another user’s observations. For example, if someone identified the genus of a plant, and you know the species, you can suggest that species. When an identification is precise enough and has community support, it can become “research grade” and used in science data banks. To get others to review your photos, add as much detail as possible and make sure your settings are set up to receive notifications.

In order to protect rare species, there is also a “geoprivacy” function. You can choose the level of geoprivacy when you submit. “Open” shows exactly where it’s located, “obscured” tells you “roughly” where it is, while “private” simply indicates the species is somewhere in Ontario. For an endangered species – the Wood Turtle, for example – iNaturalist automatically makes the location private.

Projects

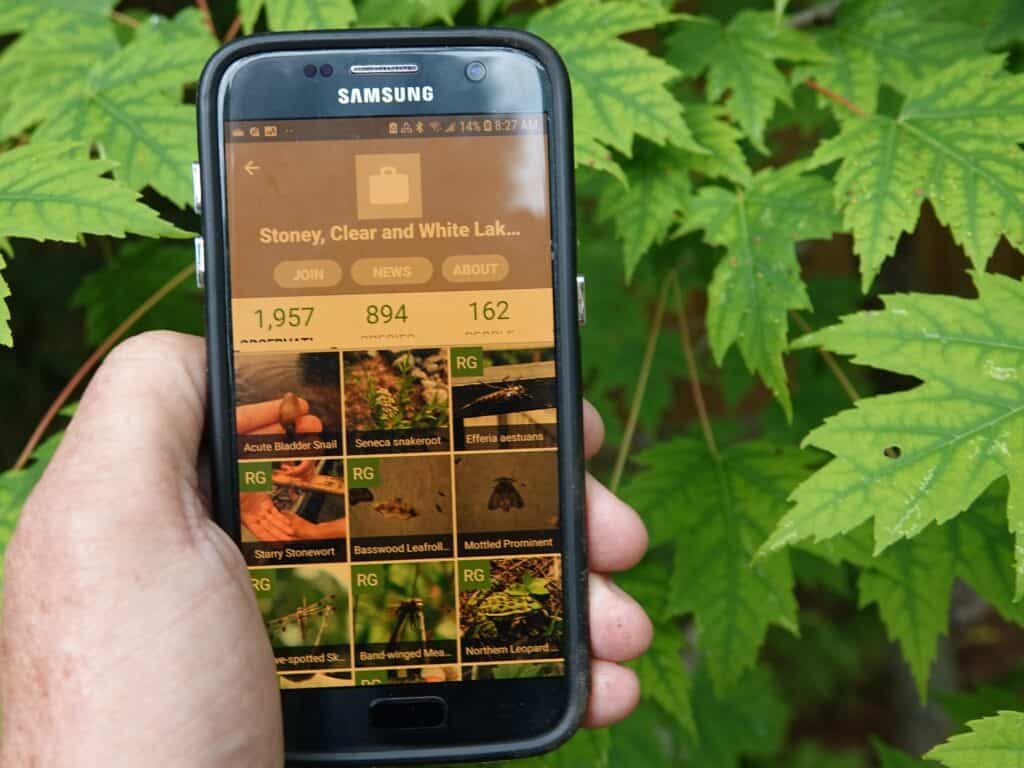

You can also join and/or set up iNaturalist projects. These are often for a specific group of species (e.g., invasive plants) or for a specific location (e.g., Stoney Lake). If you visit the page for a given project on the iNaturalist website, you can see the number of observations, species, and observers (along with their names) taking part. In the Stoney, Clear and White Lake Bioblitz project, for example, 188 observers have made over 2,600 observations and identified nearly 1,100 species.

Projects are a great way to connect to people. They are also an incentive for people to either start using iNaturalist or to make more observations. The Invasive Species in Ontario project has over 10,000 contributors! It can also be fun to set up your own property as a project. In this way you can keep track of all you’ve seen there. Just be sure that if you photograph flowers or trees that have been planted, you mark them as “captive/cultivated” from the app.

Scientific value

When I attended the iNaturalist workshop, I was surprised to learn just how valuable iNaturalist data is to the scientific community. Mike Burrell, who led the session, works on reviewing and incorporating community science data into the Natural Heritage Information Centre (NHIC) data base. NHIC tracks rare species in Ontario. He explained that data from platforms such as eBird and iNaturalist makes up nearly half of their data base.

Observations from individuals, when combined with thousands of others, can become hugely significant and even inform conservation policy. By posting an observation of an early spring lilac bloom, for example, you may be providing data showing how flowering dates are changing as the climate warns. Visitors to Algonquin Provincial Park recently snapped a picture of a Canada Lynx as it darted across a bike trail. They then submitted the photo to iNaturalist, providing one of the first confirmed lynx records for the park in recent history.

iNaturalist has also developed an introductory app called SEEK. It is primarily for kids but also fun for families who want to spend more time exploring nature together. A live view through your phone tells you what you’re looking at. Kids also earn badges for observing different types of species and participating in challenges.

At its essence, iNaturalist provides a way to reconnect with nature – something so many us are trying to do these days. It reminds us to pause and look closely at the natural world, and then to share those moments. With autumn on our doorstep, make a point of getting outside and exploring with your smartphone in hand. Who knows? Maybe you’ll even finally put a name to all those fall mushrooms you’ve wondered about for years!

CLIMATE CRISIS NEWS

Only a tiny fraction of the public feels a true sense of alarm for what is in store for us if we continue on the present climate trajectory. But even alarming people won’t necessarily inspire action. Most people need to be equally aware of reasons for hope and encouragement, hence this weekly update from both perspectives.

ALARM: The California wildfires, which have already burned 2,800 structures and 1.5 million acres, have hastened another climate crisis: homeowners who can’t get insurance. Because of the staggering losses insurers face, they have been pulling back from the huge swath of fire-prone areas across the state. The insurance crisis is making California a test case for the financial dangers of climate change, as wildfires, floods, hurricanes, and other disasters create economic shockwaves around the world. (CO2 update: September 1 – 412 parts per million and rising. Pre-industrial Revolution – 280 ppm. Highest safe level – 350 ppm)

ENCOURAGEMENT: A British firm hopes by the end of 2020 to begin manufacturing the world’s most efficient solar panels. Oxford PV claims that its panels will be able to generate almost a third more electricity than traditional silicon-based solar panels. This is achieved by coating the panels with a thin layer of a crystal material called perovskite. The breakthrough represents the biggest improvement in solar power generation since the technology emerged in the 1950s.

For local climate news and ways to take action, go to https://forourgrandchildren.ca/ and subscribe to the newsletter. For Our Grandchildren is also on Facebook.