Peterborough Examiner – December 10, 2021 – by Drew Monkman

The solstice reminds us why we have seasons

One of the greatest pleasures to be derived from the regular observation of the natural world is to witness the passage of time as one season slowly slips into the next. Like a celestial clock, events in nature tick off the time year.

The predictability of each new season provides a much-needed source of stability in our lives. We know with high certainty what the natural world has in store: the reoccurrence every spring, summer, fall, and winter of the same natural events. Knowing this provides a reassuring counterbalance to the onslaught of change and uncertainty that characterizes modern life. The seasons teach us that all things must pass but that most things shall return. They also teach us about transitions – a reality of most every aspect of human life.

The very cornerstone of most plant and animal identification is knowing what to expect, given the season at hand. As just one example, in early winter I know that any small bird I see will likely be one of just 20 species. Having this knowledge makes identification far easier.

Solstice science

As the winter solstice approaches, my sense of seasonal change is more acute than at any other time of year. The profound silence of the woods, the absence of smells, the lack of vibrant colours, the cold weather, and the short days all contribute to a visceral feeling of fall ending and winter taking centre stage.

The solstice this year occurs on December 21 and marks the first official day of winter. It’s actually not a whole day, however, but simply the brief moment when the sun is exactly over the Tropic of Capricorn in the Southern Hemisphere. I like to imagine myself out in space casting an eye down on our blue planet and seeing how the northern hemisphere tilts at its greatest angle away from the sun. The solstice is a tangible reminder that we earthlings are indeed passengers on a body of rock and water orbiting a luminous sphere of hot glowing gas.

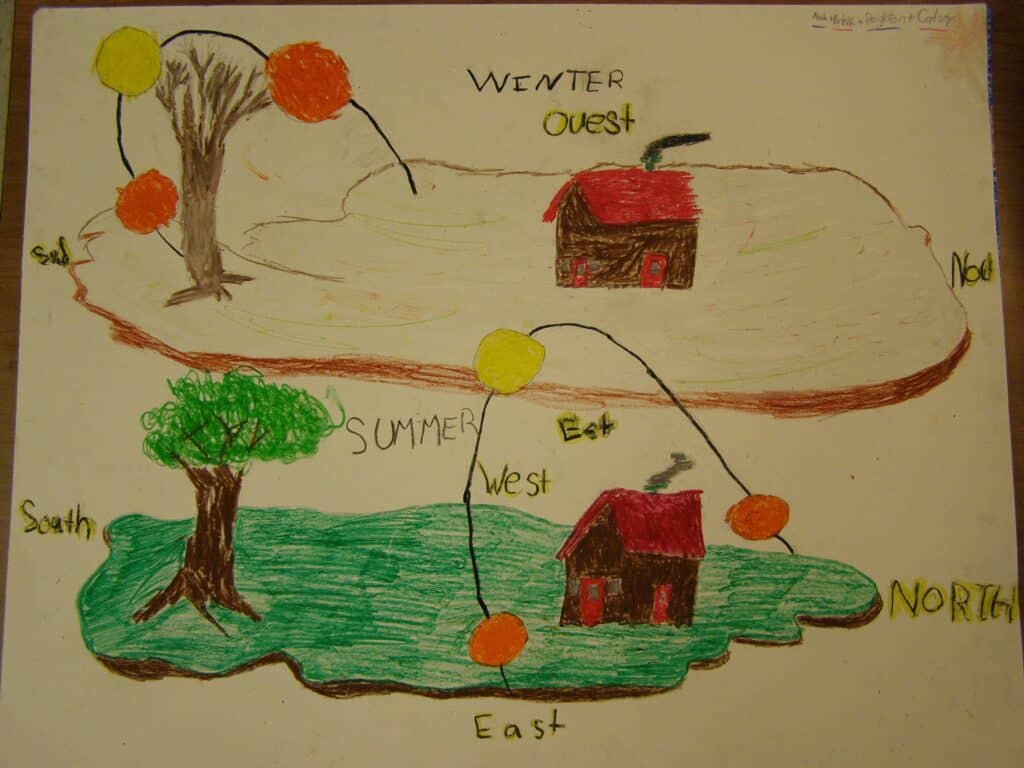

It also reminds us of why we have seasons. Think of our planet as a spinning top, tilted at an angle of 23-and-a-half degrees. As Earth cruises through space, the northern hemisphere leans towards the sun for part of the year – our summer – and away from the sun for part of the year – our winter. In fall and spring, Earth is intermediate between these two positions. This tilt causes a huge difference in the amount of heating our planet’s surface receives from one season to the next.

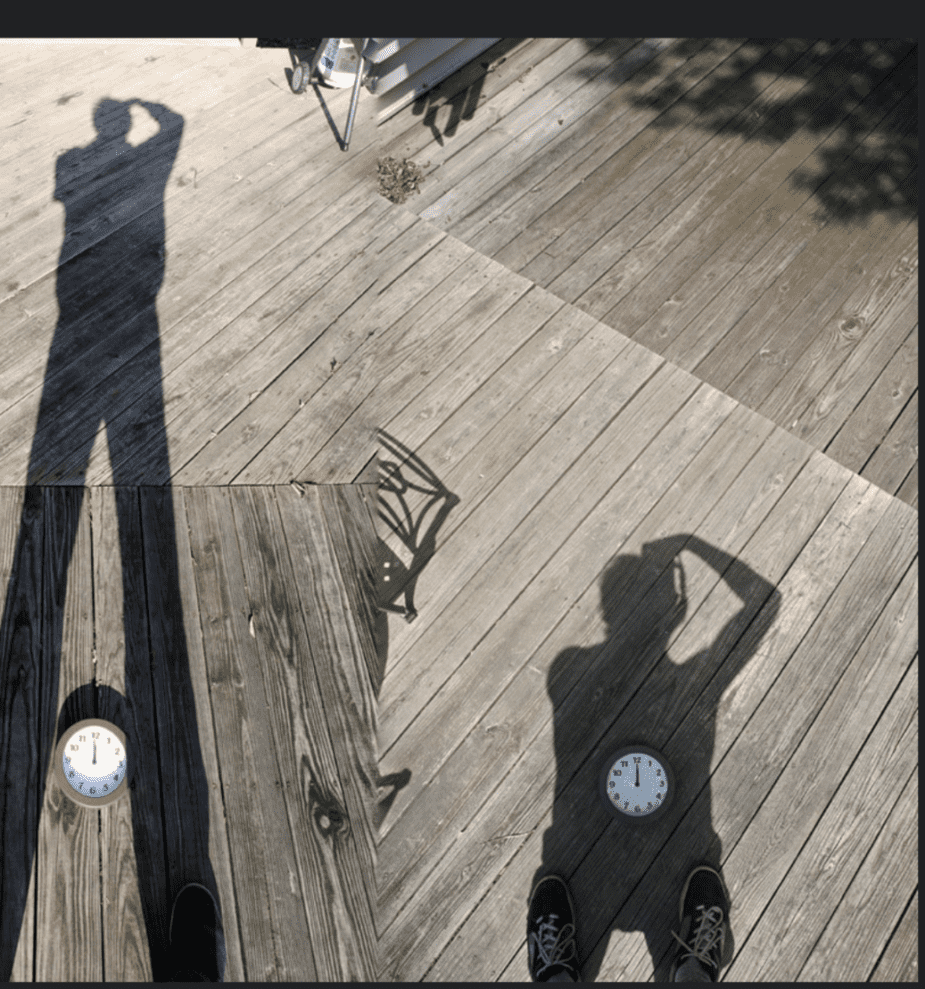

At the summer solstice in June, sunlight strikes the northern hemisphere almost perpendicularly at noon. The sun is nearly overhead, and heating is fast and efficient. This also means that our noontime shadow is very short. Winter sunlight, however, arrives at a much shallower angle and closer to horizontal. Because the light also scatters over a larger area, far less heating occurs. With the sun relatively low in the sky, our mid-day shadow is a full three times as long as it was in early summer.

With sunrise not until 7:45 and sunset at 4:37, this is a great time of year to see exactly where the sun rises and sets. Right now, it’s at its furthest point south. Head to a high open area with an unobstructed view of the eastern and western horizon. Armour Hill and Ackison Drive north of Lily Lake Road are two good locations in Peterborough. Take note of exactly where the sun rises and/or sets in relation to landmarks such as trees or buildings. At noon, look at how low the sun is in the sky. Do the same at the spring equinox, summer solstice and fall equinox, making sure to stand in the same spot. You will be amazed by how much the sunrise and sunset points and the sun’s noontime altitude change with each new season. You’ll also gain a better understanding of why we have seasons.

If you head out this month to watch sunset, take a moment afterwards to look up and appreciate the sprawling Orion constellation, the Pleiades, and Sirius, the brightest star of any season.

Why the solstice matters

For ancient peoples with no knowledge of science or the movement of celestial bodies, we can easily imagine that the solstice was a time of profound emotion. Neolithic farmers, whose lives were intimately tied to the cycle of the harvest, were closely attuned to the movements of the sun. They would see the sun rising and setting further south each day, notice the diminishing hours of daylight, and struggle to stay warm in the increasing cold. They would almost certainly have feared the sun’s complete disappearance. However, just when the world appeared to be on the brink of utter darkness and oblivion, the sun would suddenly stop its southward march in sunrise and sunset points. Its mid-day elevation, too, would cease to slip lower and lower in the sky. The sun would appear to stand still before once again moving northward and climbing higher in the sky. No wonder it became a time of rejoicing and is intimately linked to our own celebration of Christmas.

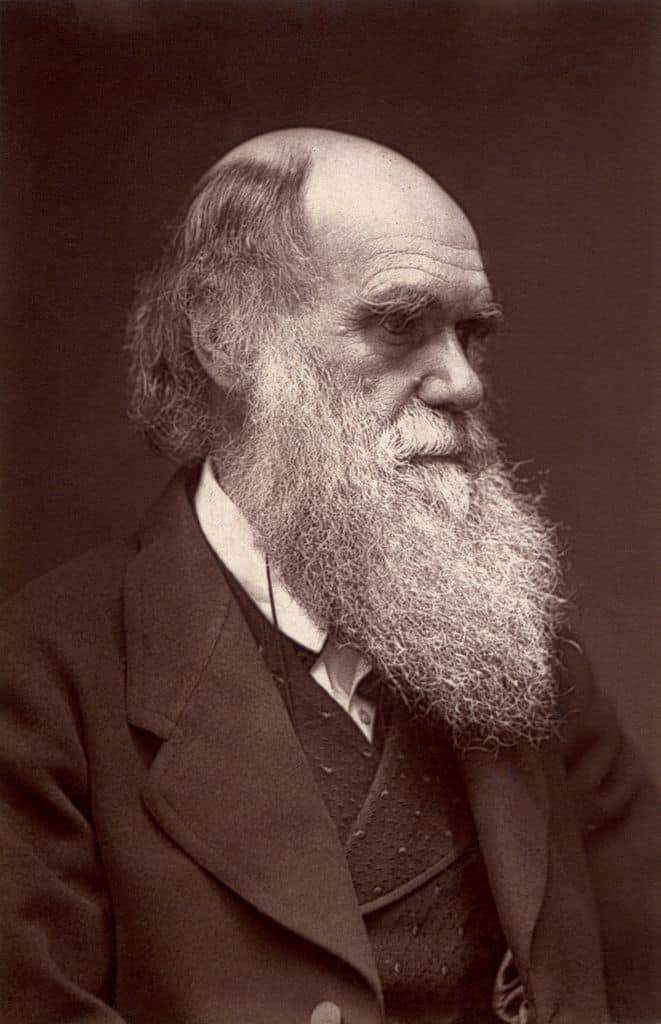

The solstice is also a time of contemplation and reverence. The word itself means “the point at which the sun stands still.” Thanks to Copernicus, we now know that the sun itself does not move, at least not in relationship to Earth. The very fact that we continue to use the word “solstice” – even in the face of its scientific inaccuracy – should remind all of us how far humanity has come in our understanding of the world. What better time than now to give a tip of the hat to the great scientists – Copernicus, Galileo, Newton, Darwin, Einstein, Curie, and many more – who challenged the status quo and rescued us from myth and superstition. Embracing science is more important than ever when we consider the egregious denial of scientific facts around Covid and climate change that is so rampant these days.

CLIMATE CHAOS UPDATE

HOPE: According to a new International Energy Association Report (IEA) report, renewable electricity growth is accelerating faster than ever worldwide. Renewables are set to account for almost 95% of the increase in global power capacity through 2026, with solar PV alone providing more than half. See https://tinyurl.com/y6f5ubxp

CO2: A key measure of how much climate progress the world is making is the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) in parts per million (ppm) in the atmosphere and whether it is rising. The pre-industrial level was 280 ppm and the highest level deemed safe is 350 ppm. The graphic below shows the frightening current readings.

TAKE ACTION: To see a list of ways YOU can take climate action, go to https://forourgrandchildren.ca/ and click on an ACTION button.