Costa Rica is not just about dazzling nature; it’s also about great people

Peterborough Examiner – August 12, 2022 – by Drew Monkman

My morning Costa Rican routine is always the same: get up at dawn, hop on my bike, and head out to enjoy the peak hours of bird activity. Invariably, an exciting experience awaits me. If not a new bird or an amazing photo op, then maybe meeting a local resident who goes out of their way to help me find a bird. People also love telling me what other wildlife might be around. This is how I learned about the location of a great green macaw nest from Luis, who lived nearby. He even invited my wife and I to come for a tour of his beautiful tropical garden and to get close-up views of agoutis – a large rodent – that he feeds.

It’s experiences such as these that had brought us back this winter to the Puerto Viejo area on Costa Rica’s southern Caribbean coast.

Bill and Ricky

One advantage of returning to the same area each year is getting to know local “Ticos” (native Costa Ricans) and regular visitors like my American friend, Bill Sedivy. Bill spends half the year in Costa Rica and the other half guiding river rafting tours in Idaho and surrounding states. Quite the life! I’ve also gotten to know Bill’s close friend and birding partner, Alric Emory Allen-Lewis. Better known as Ricky, he is Afro-Costa Rican and has a wealth of knowledge about every aspect of local birds, plants, culture and history. His family has lived here for generations and his grandmother was indigenous. I’ve learned so much from Ricky like which trees attract which birds, how chewing the leaves of jackass bitters (Neurolaena lobata) gives you energy, and that when the dragonblood trees (Pterocarpus officinalis) are in flower, turtles will be coming ashore to nest.

Bill, Ricky and I have birded numerous times together. This year, we had a great morning in and around the tiny Afro-Caribbean town of Manzanillo. We found 50 species including a locally-rare streak-chested antpitta. On another occasion, we explored part of Puerto Vargas Road at the entrance to Cahuita National Park. Our first birds of the morning – three black-chested jays – were the most memorable. We watched with amazement as one of the jays pecked at a vine snake it had just caught. The snake was at least five times the length of the bird. We were also enthralled by a hundred or more broad-winged hawks soaring just above the tree tops as they migrated north. Unfortunately, Cahuita National Park is not birder-friendly. It doesn’t even open until 8 am when the best morning bird activity is almost finished.

Casa Calateas

Bill and I also had an exceptional morning of birding at Casa Calateas, located on the mountain-side near Cahuita. Our friend Jason Westlake, who owns a yoga retreat, had arranged for a guide. To fully appreciate the wealth of Costa Rican birds, many of which are secretive and only found by knowing their song, a guide is a must. Costa Rican guides are highly trained and most are licensed by the government. Not only do they know and can often imitate all the vocalizations, but they have the knack of getting their spotting scope on birds in a matter of seconds. Jason found us a great guide in Erick Vargas.

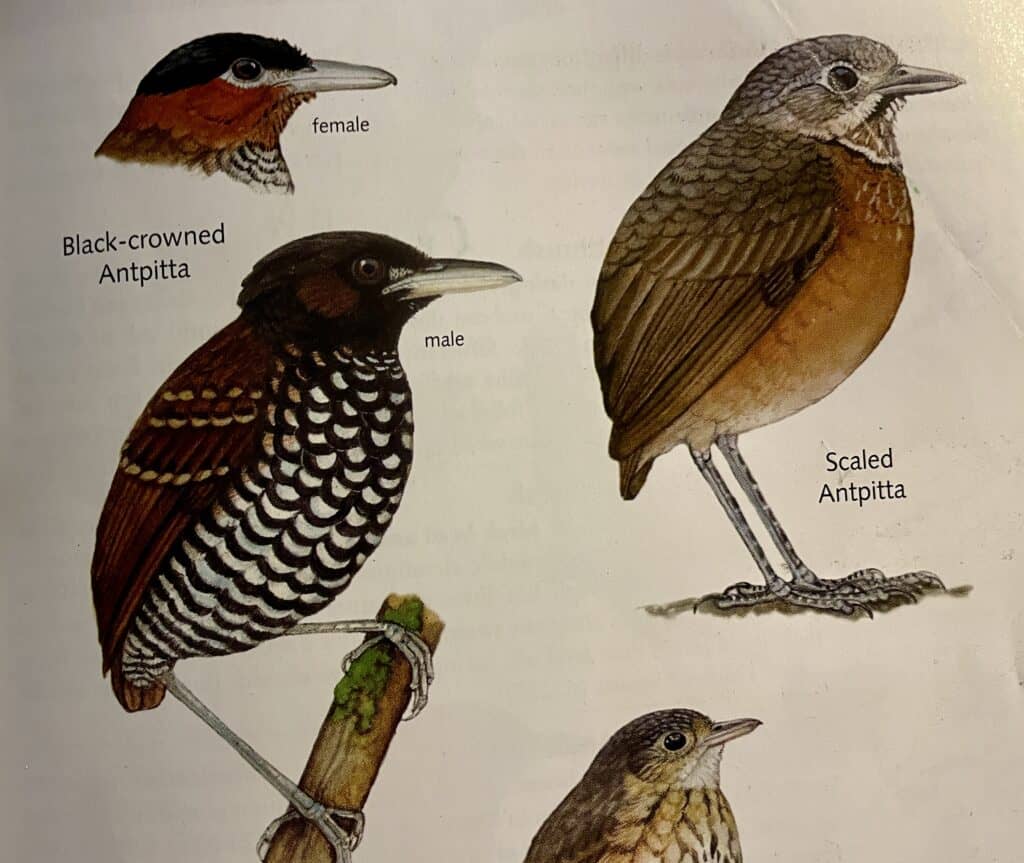

It was a quintessential Costa Rican morning with sunny but cool weather, rich forest habitat, and abundant bird song. Our target bird was the black-crowned antpitta. Other than Erick, none of us had ever seen one. Antpittas are small, plump, long-legged birds that tend to be shy and excruciatingly difficult to see in the dim rainforest understory.

As we walked along the road, Erick played a recording of the antpitta’s ridiculously long-lasting call. Suddenly, one answered back. We were ecstatic. He eventually coaxed it out near the roadside where we got frustrating, partial views as it lurked about, half-hidden behind a log. Finally, it scurried across the road in plain sight. High-fives were shared by all.

At the road’s end, a rickety platform afforded a sensational view of a huge valley. We spent at least an hour watching soaring swifts, hawks, kites, and even a majestic king vulture – all against a backdrop of cloud-shrouded mountain tops and mostly unbroken forest. All the while, we were entertained by another life bird for me, a white-fronted nunbird. Its loud, varied repertoire of sounds never stopped. To cap things off, a stunning male red-capped manakin posed only metres away for at least two minutes. With five life birds and 15 new species for the trip, I decided to set a goal of finding 200 species before heading home to Canada.

I was so enamoured by Calateas that I returned a second time with Jason and Erick. One of many highlights was identifying 10 different species in one fruit-laden tree. They included everything from North America-bound red-eyed vireos and chestnut-sided warblers to spectacular resident species like golden-hooded tanagers and both green and shining honeycreepers. We were also treated to a majestic black hawk-eagle soaring over the observation deck. The hawk-eagle was one of six life birds for the day and brought me to 146 species for the trip.

Moving to Cahuita

On March 13, we moved to our second rental house, this one located about a half-hour bike ride west of Cahuita near the beautiful Passion Fruit Ecolodge. The house was quite secluded and set among towering fig trees with huge, sprawling buttress roots. The property rang out with the songs of woodcreepers, aracaris, fruit crows, and oropendolas by day and pauraques (a close relative of whip-poor-wills), spectacled owls, and huge cane toads by night.

As at the first house, I made a point of chatting with the gardener, Francisco. Like so many Ticos, he was quite knowledgeable about local nature. He said I needed to return when the “chilamate” fig trees are in fruit. He described a non-stop feeding frenzy with everything from turkey-like crested guans to monkey-like kinkajous. And, like so many people I’ve met here over the years, he went out of his way to help me. When I told him my bike had a flat tire, he jumped on his motorcycle and went into town to purchase a new inner tube and pump. He repaired the flat in a flash and I had to twist his arm to take any money for his expenses.

Sandra Candela

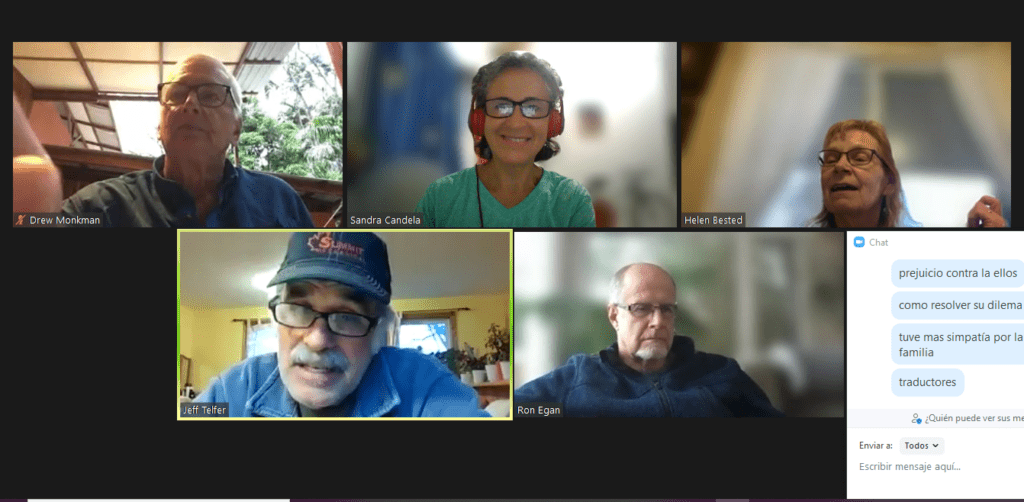

My passion for learning Spanish began with wanting to get information from local people when out birding. However, it soon grew into a fascination with not only the language itself but Latin American culture in general. The investment in time and effort has paid off in spades. I must give much of the credit to having found an excellent Spanish teacher, Sandra Candela, who lives in Cahuita. She is also a consultant on sustainable agriculture and cacao agroforestry and sells cacao products like nibs and dehydrated beans.

I meet up with Sandra both in Costa Rica and over Skype from home. She continues to help with the still-challenging ins and outs of the language, especially Costa Rican idiosyncrasies like the many ways to use the famous term “pura vida”. It’s as much an emotion and attitude as it is a saying.

I’ve also learned a great deal from her about local indigenous and Afro-Costa Rican culture, cacao and all its derivatives, Tico politics, and how climate change is impacting the Puerto Viejo region. This includes quickly rising sea levels with shrinking beaches, a huge loss of beach-side palms, more frequent and longer droughts, and how farming is so much more precarious since traditional rain patterns no longer apply.

I’ll wrap up this series next week with my most unforgettable Costa Rican experience ever.

Practicing Spanish with Sandra Candela in person (left) and on Skype with my language group. (DM)