Almost any time you’re near water in summer, you’re bound to see dragonflies and damselflies. They sometimes even show up in your garden. Thanks to their abundance, diversity, striking colours and relative tameness, they make for an ideal group of invertebrates to watch, identify and, for more and more people, photograph. With names like Ebony Jewelwing, Stygian Shadowdragon and Racket-tailed Emerald, how could anyone NOT want to learn more about these amazing creatures?

When we look into the huge eyes of these insects, we are seeing life as it existed millions of years ago. Odonates (a collective name for dragonflies and damselflies) are as old as the first reptiles and far older than the first flowering plants. Their basic structure has hardly changed in all this time. This is because evolution actually slows down, when organisms become well adapted to a stable environment. Now, like then, an Odonate’s head consists of two large compound eyes and three simple eyes. The antennae are minute and hair‑like. Adults have biting mouthparts and two pairs of similar‑sized, net‑veined wings. The abdomen is long, slender and divided into segments. Odonates are opportunistic predators, meaning they will try to catch and eat just about anything. This includes mosquitoes, flies, midges, moths and even others of their own kind.

Odonates of the Kawarthas

Our knowledge of our local Odonates dates only back to 1993 when a small group of local naturalists began keeping detailed records of their sightings. Now, over 100 species have been recorded in Peterborough County alone, approximately one-third of which are damselflies.Like butterflies, different species of Odonates fly at different times of the year. In July, some of the most common and easy-to-identify dragonflies are the “skimmers”, a group characterized by strong wing and body markings. They include the Dot-tailed Whiteface, Common Whitetail, Chalk-fronted Skimmer, Four-spotted Skimmer, Twelve-spotted Skimmer and Widow Skimmer. The Common Green Darner and Canada Darner are also easy to find. Later in the summer, small dragonflies called meadowhawks become very common. In most species, the males are red, while the females and immatures are yellow.

As for damselflies, watch for Ebony Jewelwings, Common Spreadwings, Eastern Forktails and the various bluets. The latter are powder blue in colour and are often seen on marsh vegetation and around cottage docks.

It is quite common to find dragonflies feeding in large groups. Species such as Canada Darners are often attracted to swarms of other insects such as flying ants. Chalk-fronted Skimmers can also be found in impressive concentrations. I saw thousands in late June at Big Gull Lake, north of Kaladar. They were seemingly everywhere – along the cottage road, on the dock, on the picnic table, etc. Dozens would fly up together from the road each time a car passed and then immediately return to perch horizontally on the ground.

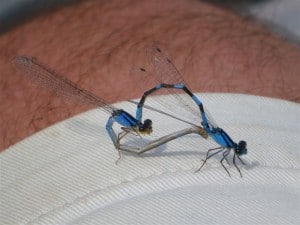

Odonate sex

One of the most interesting and noticeable Odonate behaviours is mating. There are three stages involved. First, the male bends his abdomen beneath him in order to transfer sperm from genitalia at the tip of the abdomen to secondary sex organs located near the junction of the abdomen and thorax. Next, he forms a tandem with the female by literally grabbing her behind the head, using claspers located at the tip of his abdomen. The pair then alights and forms a “wheel” position. If she accepts the male, she will bend the tip of her abdomen around until her genitalia are brought into contact with the male’s secondary sex organs. Now, this is where things get even more interesting. He often then uses special “scoopers” to clear out any sperm that a previous male may have deposited in the female. This helps to assure that only his genes will be transferred to future generations. Having cleaned house, the male injects his sperm into the female, and the wheel position is broken. To keep rival suitors away, males of most species will actively guard their mate until she has finished laying her eggs in the water. In some Odonates, the male actually retains the female in his hold until egg-laying is completed. You can often see pairs flying attached together in this manner.

The larvae that emerge from the eggs are aquatic and develop without a pupa (resting stage). They have a unique lower “lip” which serves as an extendible, biting organ for feeding. Equipped with hooks, it is a formidable tool at capturing prey such as the larvae of other insects. The larval stage lasts anywhere from one month to five years, depending on the species. When the larva is ready, it crawls out of the water onto a support such as a rock or plant stem. Its cuticle splits along the back of the thorax and the adult slowly emerges from the larval skeleton. Soft but complete, the dragonfly or damselfly then spends the next hour pumping blood into its wings, which expand and harden. The glistening immature adult then flies off, leaving behind the larval skin, or exuvia. Adults will not develop their true colours for a few weeks. During this time, they often frequent upland habitats far from water and are sometimes even seen clinging to trees and walls.

Identification

Dragonflies and damselflies are easy to tell apart. Damselflies tend to be small – often only an inch or so in length – with a thin body. They are weak fliers. Damselflies hold their wings closed or only partially spread when at rest. Dragonflies, on the other hand, have thick bodies, are strong fliers and keep their wings completely open when resting.

Fortunately, many Odonates can be readily identified in the field, often just with the naked eye. For the more skittish varieties, a pair of binoculars comes in handy, especially if you have a pair that can close-focus to one or two metres. You can also take a picture of the insect and identify it later. Because some species rarely land (e.g., darners), a butterfly net can also come in handy. They are fun to use, too. The dragonfly can then be carefully transferred to a viewing jar or plastic bag for identification. You can also hand‑hold the insect by gently raising all four wings and pressing them together over the thorax. Dragonflies cannot sting you.

As part of the identification process, pay attention both to field marks and to behaviours. For example, does it fly high or low? Does it perch often and, if so, how and where? Are there any special markings or colours on the wings, thorax or abdomen? Are the eyes separated or connected? It is also worth spending some time learning the key features of each of the three families of damselflies and six families of damselflies. This serves to greatly narrow down the choice of possible species. Remember, too, that the males and females of some species are very different looking, as are many of the immatures.

The Field Guide to the Dragonflies and Damselflies of Algonquin Provincial Park and the Surrounding Area is an excellent resource for anyone interested in central Ontario’s Odonates. The main author is Colin Jones, a local resident. The illustrations are by Peterborough native, Peter Burke. I would also recommend Stokes Beginners Guide to Dragonflies and Damselflies. A great on-line resource can be found at odonatacentral. Start with the checklist feature to get a list of those species found in Ontario. You can then go on to browse the photographs. A checklist of Ontario Odonata is also available by contacting the Toronto Entomologists’ Association. This website also has other great resources for the study of Odonates.