The Kawarthas is home to a fascinating variety of odonates

The buzz on our street this summer is not the usual gossip shared by neighbours. Rather, it’s the sound of mosquitoes. June’s warm, wet weather created perfect conditions for mosquito reproduction, and they took full advantage of it. Up until the last week or so, working outside was nearly impossible without some kind of bug protection. Few of us stop to think, however, that nature has its own mosquito control system – ancient flying machines that love nothing more than dining on these blood-sucking pests. Enter the odonates.

From gardeners to birders, and children to adults, dragonflies and damselflies intrigue us all. Known collectively as odonates (from the insect order Odonata), they also have evocative names like ebony jewelwing, Stygian shadowdragon and racket-tailed emerald. Odonates also keep civilized hours – most don’t become active until mid-morning – and prefer warm, sunny weather.

When we look into their huge eyes, we are seeing life as it existed millions of years ago. They are as old as the first reptiles and far older than the first flowering plants. Their basic structure has hardly changed in all this time. Clearly, evolution mastered odonate design a long time ago.

Dragonflies and damselflies are easy to tell apart. Damselflies tend to be small – often only an inch or so in length – with a thin body. They are weak, tentative fliers and hold their wings closed or only partially spread when at rest. Dragonflies, on the other hand, are much larger with thick bodies. They are also strong fliers and keep their wings completely open when resting.

Odonates of the Kawarthas

Our knowledge of the dragonflies and damselflies of the Kawarthas dates to only 1993 when a small group of local naturalists began keeping detailed records of their sightings. Now, over 100 species have been recorded in Peterborough County alone, approximately one-third of which are damselflies.

Although dragonflies and damselflies are usually found around water – marshes, in particular – they also frequent fields, roadsides and gardens. All our local rail-trails provide great odonate-watching (also known as “oding”) opportunities, especially in sections that pass through wetlands. Jackson Park, GreenUP Ecology Park, and the Imagine the Marsh Conservation Area in Lakefield (off D’eyncourt St.) are also excellent destinations for seeing odonates. Watching from a kayak or canoe can be especially fun and productive.

Like butterflies, different species fly at different times of the year. In July, some of the most common and easy-to-identify dragonflies are the “skimmers”, a group characterized by prominent wing patches and body markings. They include the painted, chalk-fronted, four-spotted, twelve-spotted, and widow skimmers as well as the Halloween pennant. Darners, too, are easy to find. The male common green darner is especially beautiful with its bright green thorax and blue abdomen. This species is migratory, with large numbers moving along the shore of Lake Ontario in early fall. By late summer, smaller dragonflies called meadowhawks become abundant. In most species, the males are red, while the females and immatures are yellow.

As for damselflies, now is a good time to see ebony jewelwings, a species that often turns up in gardens. They are quite large and, at first glance, appear almost entirely black. In the proper light, however, they radiate a beautiful metallic green lustre. Other common damselflies on the wing right now include spreadwings, forktails and bluets. The latter are tiny, powder blue damselflies, which are often seen on marsh vegetation and around docks. They love to land on fishing rods.

Interesting behaviours

Odonates attract our attention in many different ways. For example, large numbers of the same species often emerge at the same time. Black and white chalk-fronted skimmers are typical in this regard. In early summer, hundreds often congregate along cottage roads. They fly up each time a car passes and then immediately return to land on the road surface. Later in the summer, you’ll often see swarms of dragonflies feeding on flying ants. Dozens of ant-eating Canada darners entertained us for hours one summer as we sat on the dock at my brother’s cottage.

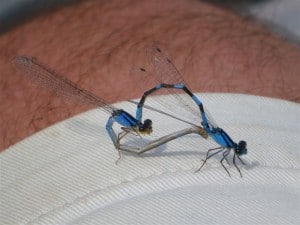

The rough-and-tumble world of odonate sex is especially fascinating. If you’ve ever seen a pair of mating dragonflies in the act, you probably have an idea of how much flexibility is required. First, the male bends his abdomen beneath him to transfer sperm from its production site near the tip of the abdomen to a slit in the penis, which is located near the junction of the abdomen and thorax. Next, he forms a tandem with the female by literally grabbing her behind the head with claspers, which are also located at the tip of his abdomen. The pair then alights and goes into the “wheel” position. To do so, the female bends the tip of her abdomen around until her genitalia are brought into contact with the male’s penis. In this way, the couple forms a closed circle with their bodies. Now, this is where things get even more interesting. The male will then use special “scoopers” to clear out any sperm that a previous male may have deposited in the female. This helps to assure that only his genes will be transferred to future generations. Having cleaned house, he injects his sperm into the female, and the wheel is broken. To keep rival suitors away, some males will actively guard their mate – or even retain her in their hold – until she has finished depositing her eggs in the water.

Photography

Odonates are among the most photogenic of our insects. Many species also have the cooperative habit of returning to the same perch time and time again. You can therefore pre-focus on the perch and wait for the dragonfly or damselfly to land. All that’s required is some patience. Although a macro lens provides the best results, you can still get good pictures with a standard telephoto lens.

Try to take advantage of the softer, diffused light of cloudy days when odonates are less active and easier to approach. For species like darners that don’t often land, you can sometimes find them perched during the cool temperatures of early morning before their flight muscles warm up. You might even find a few covered in dew. Always focus on the eyes and take shots from different angles. Some of the most satisfying pictures can be achieved by shooting the dragonfly from the side with the camera’s sensor parallel to the insect’s body. Whenever possible, look for a background that contrasts with the colours of the dragonfly.

Taking a picture is also useful for identification purposes. Although most species are relatively easy to identify with a guidebook or website photo (see below), you can also upload the picture to iNaturalist.org where someone else will identify it for you.

Viewing and identifying

Almost everything that applies to butterfly-watching is also true for oding. Many species can be readily identified with the naked eye. For the more skittish varieties, however, a pair of close-focusing binoculars is a must.

Because some species rarely land, a butterfly net can also come in handy. A net is also fun to use, especially if you’re trying to catch a dragonfly in a swarm. Once you’ve caught it, transfer the insect to a jar or Zip-lock bag for closeup viewing. Another option is to hold the dragonfly in your hand by placing your thumb and index finger on either side of the thorax and then gently move your fingers upwards. Pinch all four wings together over the body between your fingers.

I also recommend purchasing a copy of the “Field Guide to the Dragonflies and Damselflies of Algonquin Provincial Park and the Surrounding Area”. It is an excellent resource and includes all the species found in the Kawarthas. The main author is Colin Jones, a local naturalist and biologist. The beautiful illustrations are by Peterborough native, Peter Burke. A great on-line resource can be found at www.odonatacentral.org. Start with the checklist feature to get a list of those species found in Ontario. You can then go on to browse the photographs. A checklist of Ontario Odonata is also available by contacting the Toronto Entomologists’ Association at www.ontarioinsects.org

Spend some time learning the key field marks and behaviours of each of the three families of damselflies and six families of damselflies. For example, are the eyes separated or connected? Are the wings clear or patterned? Does it fly high or low? Does it perch often and, if so, how and where? Remember, too, that the males and females of some species can look quite different, as can some of the immatures.

Odonate-watching can become a fascinating hobby. You’ll soon be enamored by their jewel-like colours, their intriguing behaviours and the challenge of finding new species. As with butterflies, the odonates are yet another window onto the amazing biodiversity of the Kawarthas.

Climate Crisis News

Climate alarm bells just keep on ringing. Boosted by a historic heat wave in Europe with temperatures reaching 45.9 C in France, Earth just registered its warmest June ever. July is on track to set a new heat record as well. Unprecedented warming is also continuing unabated in the Arctic. This past Sunday, Canadian Forces Station Alert, located at the tip of Ellesmere Island, hit a record 21 C, which was warmer than Victoria, B.C. The normal is 7 C. For a sobering overview of just how serious the climate crisis is – and what can be done about it – pick up the August issue of MacLean’s magazine. It includes a 26-page section entitled “The Climate Crisis. And how to stop it.”